THE STORY OF TRURO WATER

By Bert Biscoe

They say, in the gloomier, more prosaic corridors that we are never more than six feet away from a rat! Living as we do in Truro between three rivers (the Allen, Kenwyn and Glasteinan) which merge to form Truro River which itself forms an arm of the Fal Estuary, and with much of the tributary and estuarial systems under tarmac or concrete (or, in older cases, under compressed sheepskins and sandstone or granite), the dictum may well be true. Suffice it to say that until the early 1960s, there was a causal link between our environment and health.

I live in Lower Rosewin Row, just opposite a well which was sealed up in the 1850s by Drs Carlyon and Barham as part of an innovative exercise to manage the environment and to stem the persistent invasion and contagion of cholera, ‘fever’ and smallpox. Epidemics swept through Truro regularly, particularly in thre areas of Tippet’s Back (behind River Street) and Truro Vean (north of St Clement Street). The two doctors’ experiment was successful. They prevented people living in crowded and very poor housing taking water for daily use from a common well, and this had the desired effect. Just as the hospital in which Carlyon and Barham practised, built by public subscription at the end of the C18th changed the prospects for Cornish miners, so their public health work changed the prospects for the factory workers, the tanners, stevedores and artisans of C19th Truro. Indeed, their work was so well recorded and publicised, that the approach they pioneered was copied throughout the UK.

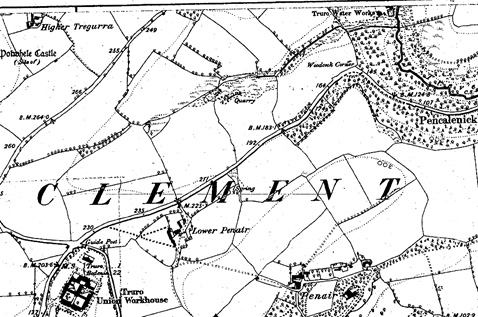

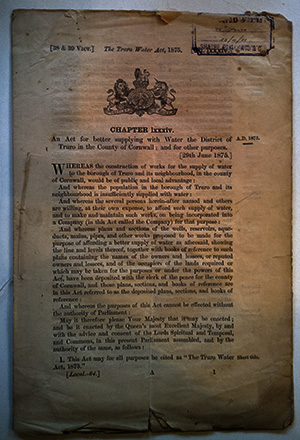

In 1873 a new Public Health Act became law. This removed power from the Improvements Commission and placed responsibility in the hands of the Borough Council. It was faced with the twin problems of sewage disposal and water supply. By 1875, after a debate about rival schemes, one to pump from Bosvigo Bridge advanced by the Council, the other to pump from Trevellas Stream at Tregurra, promoted by a private company – Truro Waterworks Company – the Truro Private Water Company Bill was passed in the House of Lords. Works proceeded.

In 1873 a new Public Health Act became law. This removed power from the Improvements Commission and placed responsibility in the hands of the Borough Council. It was faced with the twin problems of sewage disposal and water supply. By 1875, after a debate about rival schemes, one to pump from Bosvigo Bridge advanced by the Council, the other to pump from Trevellas Stream at Tregurra, promoted by a private company – Truro Waterworks Company – the Truro Private Water Company Bill was passed in the House of Lords. Works proceeded.

The Company had permission to build:

‘A pumping station, with tank, filters, filter beds, engine and boiler house, and all other necessary works and conveniences, to be situate in the said field number nine hundred and sixty seven.’

And:

‘A reservoir, with all convenient approaches, embankments, stand-pipes, valves, sluices, pipes, drains, conduits and other works and conveniences connected therewith, in a field belonging to Cordelia Vivian and Reverend John Vivian Vivian, and in the occupation of George Cliff, being the field adjoining the turnpipke gate-house on the London Road from Truro, on the north-west side thereof, opposite to the union workhouse;

And

‘A service main or line of pipes commencing in the reservoir lastly before described, and terminating at the lower end of the Tregolls Road at or near the Union Hotel’.

The Company held capital of £16,000. The Act enabled the Company to acquire the land necessary for these works ‘by compulsion’. Any subsequent purchases would not be thus enabled.

The Company was required under the Act to:

‘…provide a constant supply of water at such a pressure as can be afforded by the pipes communicating with their service reservoir’.

Clause 34 stated:

‘The Company shall at the request of every person entitled under this Act to demand a supply of water, furnish to the occupier of every dwelling-house or part of a dwelling-house to which the request relates to within the limits in that behalf of this Act a sufficient supply of wholesome water for the domestic purposes (including one watercloset) of every such occupier’.

‘Where the annual value (ie the rateable value) of the premises does not exceed six pounds, at a rate not exceeding twopence per week’. (8/6d or £0.42p per year).

Whilst able to sell water commercially the Company was obliged to ensure that its domestic customers had the priority.

It appears that the current covered reservoir was the subject of a further amending Act in 1905.

If you go to what is now Dunelm, which at one time formed part of Vineyards Farm, and which previously formed part of Gwel Quoniam, a medieval Great Field, you will observe two grass-topped mounds with inspection chambers atop. These are the covered reservoir. They remain on standby, and are flushed about once every two weeks.

Quite recently, in the 1990s, a scandal preoccupied the Environmental Health Department of the former Carrick District Council, when a badly formed sewerage connection from a new development caused blockages in the sewage pipes serving a larger estate, Bedruthan Avenue, which had been constructed in the 1970s. Much of the pipework was pitch-fibre and had been laid through private gardens. This meant that the liability for repairing the main sewer rested with the homeowners.

Tenacious work by two residents not only succeeded in ultimately removing this liability, but also secured a contribution to the cost from South West Water because it was using the combined road drainage and sewerage system to flush the Newquay Road water tanks on a regular basis. I note this partly in order to record the issue, and to recognise the work of the two residents who skilfully led the community’s battle, and partly to show that the infrastructure of the C19th still plays an important part in the everyday life of Truro.

The 1873 Public Health Act led to action to provide good quality water to the town. The waterworks has been sold and converted to a dwelling. The structure is largely recognisable as the building for which plans exist in the Cornwall Records Office. The Trevellas stream which was the main source of supply for the waterworks, lies below the Tregurra park and ride.

A visit to H L Douch’s Book of Truro offers a blunt description of how the Kenwyn and the Allen were abused and polluted by generations of Truronians. Standing at the parapet of Old Bridge today on most summer’s days, with the tide running, one can observe teeming shoals of mullet – a testament to the changed condition of this major waterway. Neither river provides power or waste disposal in the way that it did.

However, times are constantly changing and, just as the mercantile and manufacturing town of Truro relied on its rivers to drive its undershot waterwheels and to feed to tanning trade, so it is as well to have a basic understanding of how, before Siblyback, Stithians or Argall Dams, Truro provided itself with clean water from Trevellas, Tregurra and Penair streams – three other watercourses which might easily lay claim to being the founding courses of modern Truro.

When I was a pupil at Treliske School I was sent to interview the manager of Truro Waterworks. I recall not knowing where I was going, and becoming anxious as my taxi driver (no doubt the fare was an extra on my Father’s already substantial bill!) searched for the Water Works – it was not a much-visited place. Eventually, we discovered it half way down in the Tregurra Valley – an elegant and functional place built at the confluence of three streams – Trevellas, Tregurra and Penair – which arose from separate springs high on the western moors and, in the case of the Penair, above St Clements.

I remember nothing of the interview or of my tour around the works but I do recall vividly the strong sense of public service which the manager of the Works conveyed – a sense of mission which imprinted itself on my memory – I can see him now, looking earnestly across his desk and driving the point home – his work was directly concerned with keeping the town supplied with clean water – the emphasis was on ‘CLEAN’! In writing this article I feel that I am fulfilling an obligation placed upon me that afternoon.