History of the Civic Society (part 1)

‘There is no surer way of determining that a town will survive unspoiled than the corporate determination of its citizens that it shall’ – Sir Alec Clifton Taylor

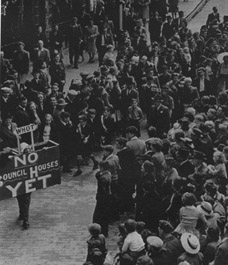

In 1962 Truro awoke to find the granite setts being uplifted and trucks from Devon coming to take them away to form the paving around its County Council offices. Truro stirred as it had not stirred since just after the War when the community  demanded of the Borough Council decent housing. Opposition was widespread and vociferous – John Betjeman phoned the County Surveyor – The Royal Fine Arts Commission wrote; workers from Harvey’s Timber Yard determined to sit on the setts to prevent their removal – the Borough Council withdrew its support for the project and it collapsed.

demanded of the Borough Council decent housing. Opposition was widespread and vociferous – John Betjeman phoned the County Surveyor – The Royal Fine Arts Commission wrote; workers from Harvey’s Timber Yard determined to sit on the setts to prevent their removal – the Borough Council withdrew its support for the project and it collapsed.

During the controversy a group of Truro’s citizens, including leading architects, councillors and aldermen, formed Truro Civic Society and affiliated to the Civic Trust. Little did they know that, fifty years later, the Society would be still campaigning to prevent the worst excesses of destruction and development, and to promote excellent architecture and design.

During the 1960s, with a demand for change emanating from its citizens, especially the young and less-well-off, Truro Borough Council determined to modernise the shopping centre. This led to the young, brash community of architects that had clustered in the town advancing a bewildering array of grand plans, and to much concern at the threat this represented to a centre dominated by late 18th and 19th century buildings.

Littlewoods replaced the Gas Showrooms, introducing a starkly modern and large frontage. The Civic Society pressed for a high quality architectural scheme. To improve the environment of the town centre and to discourage wholesale demolition, the Society encouraged a re-decoration scheme using a palette of colours to set the tone and to create unity and an attractive central shopping area, winning a Civic Trust Award for its work.

In 1967 disaster struck – the Red Lion was demolished after a serious ‘collision’ with a runaway truck. Not only had Truro lost an old, much loved and distinguished building but also a meeting place, almost a forum. The Society was tenacious in its efforts to secure a good replacement and very critical of the outcome.

In 1967 disaster struck – the Red Lion was demolished after a serious ‘collision’ with a runaway truck. Not only had Truro lost an old, much loved and distinguished building but also a meeting place, almost a forum. The Society was tenacious in its efforts to secure a good replacement and very critical of the outcome.

Neglect was as great a concern as the threat of unbridled modernity – and the Society worked hard to ensure that the Mansion House and Prince’s House were both restored properly and in full – they remain elegant enhancements and a tribute to good conservation, showing as they do, how good heritage management and business go hand-in-hand.

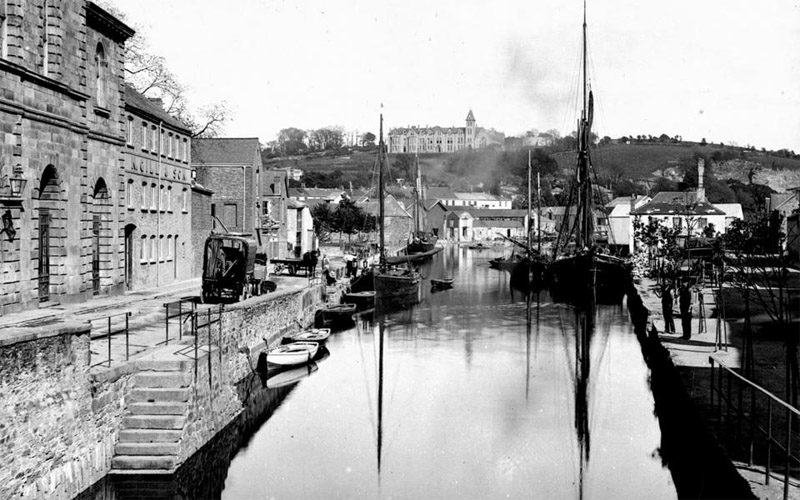

Threats abounded – Benson House was saved, as was 31 Boscawen Street (currently Santander). Barclay’s Bank was dissuaded from facing its substantial Lemon St property with reconstituted stone. Then, in 1977, one hundred years after the granting of the ‘city’ seal, and coinciding with her silver jubilee, the Queen visited. Truro Civic Society mounted a major photographic exhibition – ‘Truro – Then & Now’. The exhibition examined the town in detail, drawing attention to the all-important detail, the authenticity and the integrity of the built environment of the centre – it was a triumph, heralded by all who saw it as an influential way to ensure responsible conservation.

The architects were making their mark – John Crowther’s Martin’s Bank in Boscawen Street, and his neighbouring W H  Smith both attracted attention. So too did the New County Hall (subsequently listed) by Mike Way and the Council Architects’ Department. The Council Architects were also responsible for Truro Police Station, which nestled in the corner of the newly engineered Truro by-pass (dubbed Morlaix Avenue), creating a very modern and elegant solution to the town centre’s endemic traffic problems. In High Cross, to the consternation and distress of many people, in 1974, Truro Post Office, considered by many to be the greatest work of 19th century Truro architect, Sylvanus Trevail, was demolished to make way for Marks & Spencers. The coup of attracting this flagship store to the town was to crown the efforts of the Borough Council to modernise their town and to project Truro as Cornwall’s major retailing centre. The building, however, was not a success – standing very close to the Cathedral, it was brick-built, aggressively bland in its presence. The Civic Society struggled with the process to try and gain something special for the town but the commercial adrenaline was running.

Smith both attracted attention. So too did the New County Hall (subsequently listed) by Mike Way and the Council Architects’ Department. The Council Architects were also responsible for Truro Police Station, which nestled in the corner of the newly engineered Truro by-pass (dubbed Morlaix Avenue), creating a very modern and elegant solution to the town centre’s endemic traffic problems. In High Cross, to the consternation and distress of many people, in 1974, Truro Post Office, considered by many to be the greatest work of 19th century Truro architect, Sylvanus Trevail, was demolished to make way for Marks & Spencers. The coup of attracting this flagship store to the town was to crown the efforts of the Borough Council to modernise their town and to project Truro as Cornwall’s major retailing centre. The building, however, was not a success – standing very close to the Cathedral, it was brick-built, aggressively bland in its presence. The Civic Society struggled with the process to try and gain something special for the town but the commercial adrenaline was running.

However, the M&S building has become familiar and unnoticed. It was the focus of a significant battle after M&S moved to Lemon Quay when Society members, including Barbara Olds and Reg Bowyer, participated in a Planning Enforcement Inquiry to remove the signage of a mobile phone shop which was brash, inappropriate and without planning consent. Their success was a fillip to often sapped members as pressure was continuous as Truro’s apparent reputation as a growing retail centre spread.

In 1979 another major controversy exploded as planners and highways engineers proposed the ‘Lemon Street Crossing’ – this was intended to link Charles St and Fairmantle St to ‘complete’ the inner distributor road. It would have involved forming a ridge across Lemon Street which would have broken the line of its upward sweep, destroying its elegance and continuity, and furthermore, introducing a cross flow of traffic. Again, Truro Civic Society played a key role in the battle, combining campaigning with expertise as its membership of passionate Truronians and concerned professionals combined their energies and talents to stand up for common sense and integrity. It was a famous victory!

In 1983 the Society led and eventually achieved a reformation of the Millpool (behind the Cathedral). This included saving the workers urinal on the bridge that had served the Cathedral builders. Unfortunately, much later on, in 2009,  the Society, despite strenuous effort, was not successful in preventing the Highways Authority from removing the medieval clapper bridge (probably the oldest in Truro after the removal of the West Bridge in 1988) at the Millpool – a very significant and irreplaceable part of the town’s medieval heritage (in short supply as it is) was lost to the cause of strengthening bridges to carry 44 ton trucks (what a 44 ton truck would have been doing there was never explained – making this a scandal!

the Society, despite strenuous effort, was not successful in preventing the Highways Authority from removing the medieval clapper bridge (probably the oldest in Truro after the removal of the West Bridge in 1988) at the Millpool – a very significant and irreplaceable part of the town’s medieval heritage (in short supply as it is) was lost to the cause of strengthening bridges to carry 44 ton trucks (what a 44 ton truck would have been doing there was never explained – making this a scandal!

Also in 1983 the Society began to express concern about the loss of trees in the townscape and to demand that the interplay between buildings, streets and trees is celebrated, enhanced and properly managed. This has been a largely successful campaign which is ongoing – vigilance is constantly required!

By this time the Society was regularly consulted by the Council planners, and held a seat on the fledgling Truro Conservation Area Advisory Committee – a new idea floated by Deputy Planning Officer, Alan Rigby, and  enthusiastically supported by architects, chartered surveyors, councils and learned conservation and design bodies. In 1984 the Society brought together Truro Baptist Church and the Royal Institution of Cornwall to discuss the potential of linking the two buildings to extend the Museum whilst also enabling the Baptist Church to take over the fire-damaged Lake’s Pottery in Chapel Hill and to undertake a restoration and development which retained many aspects of the pottery whilst finding a pastoral use for the site which continues to thrive today.

enthusiastically supported by architects, chartered surveyors, councils and learned conservation and design bodies. In 1984 the Society brought together Truro Baptist Church and the Royal Institution of Cornwall to discuss the potential of linking the two buildings to extend the Museum whilst also enabling the Baptist Church to take over the fire-damaged Lake’s Pottery in Chapel Hill and to undertake a restoration and development which retained many aspects of the pottery whilst finding a pastoral use for the site which continues to thrive today.

During the mid-eighties controversy began to simmer about the future of Truro City Hall. Built as a civic centre housing the council, police, market, magistrates and fire station, it had seen many incarnations. The local government reorganisation of 1974 removed much activity from it and the successor council, Carrick District Council, paid little heed to it (and spent very little maintaining it). The Hall became a battleground – a battle in which Truro Civic Society, like most other organisations involved in shaping the town, became roughly embroiled. It was as much a matter of finding a future for the building as it was preserving it. Eventually, happily, after much hostility, the Hall for Cornwall project emerged and the City Hall became a key catalyst for crafting the future of the town centre as the internet plays havoc with traditional means of shopping and doing business.

Meanwhile, in January 1984, the Society brought together architects, surveyors, developers and planners in a conference to speak to each other! In 1985 Truro Civic Society tried to prevent the erection of ‘sheds’ at the top of Tregolls Road, on the corner with Newquay Road. Eventually, the case was lost at appeal – a lesson was learned – economic recession tends to make a priority of short-term job-creation at the expense of long-term environmental integrity and quality.

The Palace Cinema became the Society’s cause in 1986 along with perhaps the most colourful moment in the distinguished career of Steven Watson, Chief Planning Officer of Carrick District Council. This occurred when it was insisted that TESCO roof its new store at Garras Wharf with Delabole slate. TESCO said it was too expensive and took too long to deliver. A compromise – that 29% Spanish slate could be used in unobtrusive areas of the roof – led to Mr Watson taking it on himself to personally inspect the roof to ensure the right percentage of Delabole slate was used. Being a planner is not an easy job – it does not foster popularity – but Mr Watson’s judicious management of expectations – of both developers and conservationists – and his willingness to lead from the front – clambering on to TESCO’s roof, or tearing his committee off a strip for inconsistency and poor decisions – made him highly regarded by all who did business with him. Eventually the Palace was successfully refurbished, and the Britannia Inn is still in business beside the by-pass.

1988 saw two major floods in Truro and a further bundle of development projects. Mrs Armorel Carlyon was Mayor and she led the town with bravura and skill in winning a major flood alleviation scheme. She also held public meetings to demand a less fervent rush of development as part of her contribution to achieving a Local Plan for Truro. A major development of flats and moorings beside Boscawen Park, Truro River Park, was defeated.

Also in 1988, we saw the unveiling of an architectural masterpiece – the new courts on the site of Truro Livestock Market, atop Castle Hill. This was a major building, superbly executed and a genuinely original statement. Architects,  Evans and Shalev, would go on to design and execute the St Ives Tate. Unfortunately, the Government erected Pydar House next door, on the site of the old St Mary’s School in Union Street – a very dull neighbour to such a distinctive and eye-catching building. Equally unfortunate, from a cultural and commercial point of view was the closure of the market, with all its trade, its noise, its smells and bustle – Wednesdays had always been a busy day in Truro – but no more – only the judges were busy after that sad day!

Evans and Shalev, would go on to design and execute the St Ives Tate. Unfortunately, the Government erected Pydar House next door, on the site of the old St Mary’s School in Union Street – a very dull neighbour to such a distinctive and eye-catching building. Equally unfortunate, from a cultural and commercial point of view was the closure of the market, with all its trade, its noise, its smells and bustle – Wednesdays had always been a busy day in Truro – but no more – only the judges were busy after that sad day!

The Civic Society was prominent, due in much part to the new Chairman, Giles Blomfield – both architect and campaigner, Giles was a modernist who ended up as Architect to Canterbury Cathedral, having been the conceptualist responsible for the Truro Chapter House, a founding Chairman of Shelter in Truro who had built an award-winning house at Calenick in the 1960s.

The Society, under Giles Blomfield’s leadership, campaigned to reclaim the upper floors of the town centre to encourage ‘Living over the Shop’ – commercial property owners proved reluctant but townspeople saw this as a means of re-populating the town centre, addressing some of our growing housing problem, and encouraging more diversity and life into the town. The discussion continues today. An exhibition, asking people to nominate best (and worst) buildings encouraged an expansion of membership.The exhibition also gave rise to a successful campaign to retain Tremorvah Playing Foeld as a public amenity. The Society participated in the National Conference of Amenity Societies in Oxford, and was commended for its excellent relationships with local authorities!

The Society, under Giles Blomfield’s leadership, campaigned to reclaim the upper floors of the town centre to encourage ‘Living over the Shop’ – commercial property owners proved reluctant but townspeople saw this as a means of re-populating the town centre, addressing some of our growing housing problem, and encouraging more diversity and life into the town. The discussion continues today. An exhibition, asking people to nominate best (and worst) buildings encouraged an expansion of membership.The exhibition also gave rise to a successful campaign to retain Tremorvah Playing Foeld as a public amenity. The Society participated in the National Conference of Amenity Societies in Oxford, and was commended for its excellent relationships with local authorities!

And then – an explosion! The County Surveyor, responding to complaints about slippery granite pavements in Truro, started to scarify them, etching lines across the foot-worn slabs to encourage ‘grip’. Giles Blomfield demanded a meeting forthwith, and prompted this by arriving at Mr Mansell’s office. He was most forceful and won the day – the scarification of Truro’s pavements was immediately halted. If you walk down the upper reaches of Lemon Street the impact of the exercise is plain to see – if all pavements had been thus disfigured the town would have lost one of its most important distinguishing features – the colour, mass and texture of well-worn granite pavements – a 19th century symbol of civic pride and wealth.

In the early 1990s out-of-town shopping gained momentum. It was proposed to shut and sell Truro 6th Form College (the former County Grammar School for Girls). As the Borough Council discovered immediately after the War, the women of Truro are a formidable force when they collectively decide they want something – then it was council houses; in 1991 it was the retention of their old school (although many were also tempted by the attractions of Sainsburys! Again, force majeure ruled the day, although the furore did lead to a design solution which embodied at least a strong hint of the former school, as well as much of the granite facing and steps. In 1993 the School was demolished.

By 1991 the Lemon Street Crossing was coming to its denouement – an example of a challenge which led to a battle in which authorities, commercial (and mostly faceless) institutions and companies, professionals chasing fees and the ubiquitous planners were creating constant pressure for those who were determined that the town should evolve rather than be forced to grow, and should be a place of human scale fitting well into its surroundings, not too ostentatious (nodding to its non-conformist traditions), friendly, clean and safe. Fatigue was setting in, and resignation that, no matter how stern the resistance, the forces ranged against the town were simply too great. But, the town means too much to too many people, and they dug deep to sustain themselves, and the battle continued.

In 1991 the Society fought to prevent the backland between Lemon Street and Boscawen Street, behind the Royal Hotel, being developed by Sun Alliance as a covered shopping mall named ‘The Opes’ – they couldn’t even say it properly – ‘Opp’ became ‘Ope’ – hackles rose! The four phone boxes on Lemon Bridge were spot-listed; the owner of the Plaza indicated his unwillingness to sell by causing his back wall to be painted; Malletts turned down the un-refusable offer – eventually, the insurance company admitted defeat and sold the site to the Royal Hotel for less than it had paid in legal fees to cover Carrick Councils expenses.

Attention turned momentarily to discarding the intrusive and night-sky-obscuring orange sodium streetlights in favour of something more discreet, downwardly directed and environmentally efficient – Lemon Street, saved now from its crossing, was the first to be transformed as officials strove to accent their damascene conversion with sensitivity beyond the call of duty! And then, it was Sainsburys! In 1992 ‘deep concern’ was repeatedly expressed and some concessions were won.

TO BE CONTINUED